The Detectives of Everyday Life: Parenting Autistic Individuals with Intellectual Disability

Autism and intellectual disability frequently co-occur, with nearly one-third of autistic people also having intellectual disability (AIHW, 2008). Intellectual disability is characterised by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning (such as reasoning, learning, and problem-solving) and adaptive behaviour, which includes everyday social and practical skills such as communication, self-care, and managing daily tasks (APA, 2022). Language abilities in autistic individuals with intellectual disability are highly variable. While some develop fluent speech, this is less common in those with moderate to profound levels of intellectual disability, where significant language delays or minimal speech are more typical. Even when fluent speech emerges, pragmatic language difficulties are common and may persist regardless of cognitive level (Schaeffer et al., 2023). Intellectual disability is commonly classified into mild, moderate, severe, or profound levels, based on the degree of cognitive and adaptive functioning challenges (APA, 2022). While some autistic individuals with mild intellectual disability may acquire basic academic and daily living skills, those with moderate to profound disability often require lifelong assistance with communication, personal care, and decision-making. An individual’s level of intellectual disability does not capture the full variability in strengths, challenges, or support needs, but it can help describe how intellectual disability may influence development, independence, and communication. When autism and intellectual disability co-occur, it can compound challenges in language, executive functioning, and social understanding, creating a profile that is distinct from that of autistic individuals without intellectual disability.

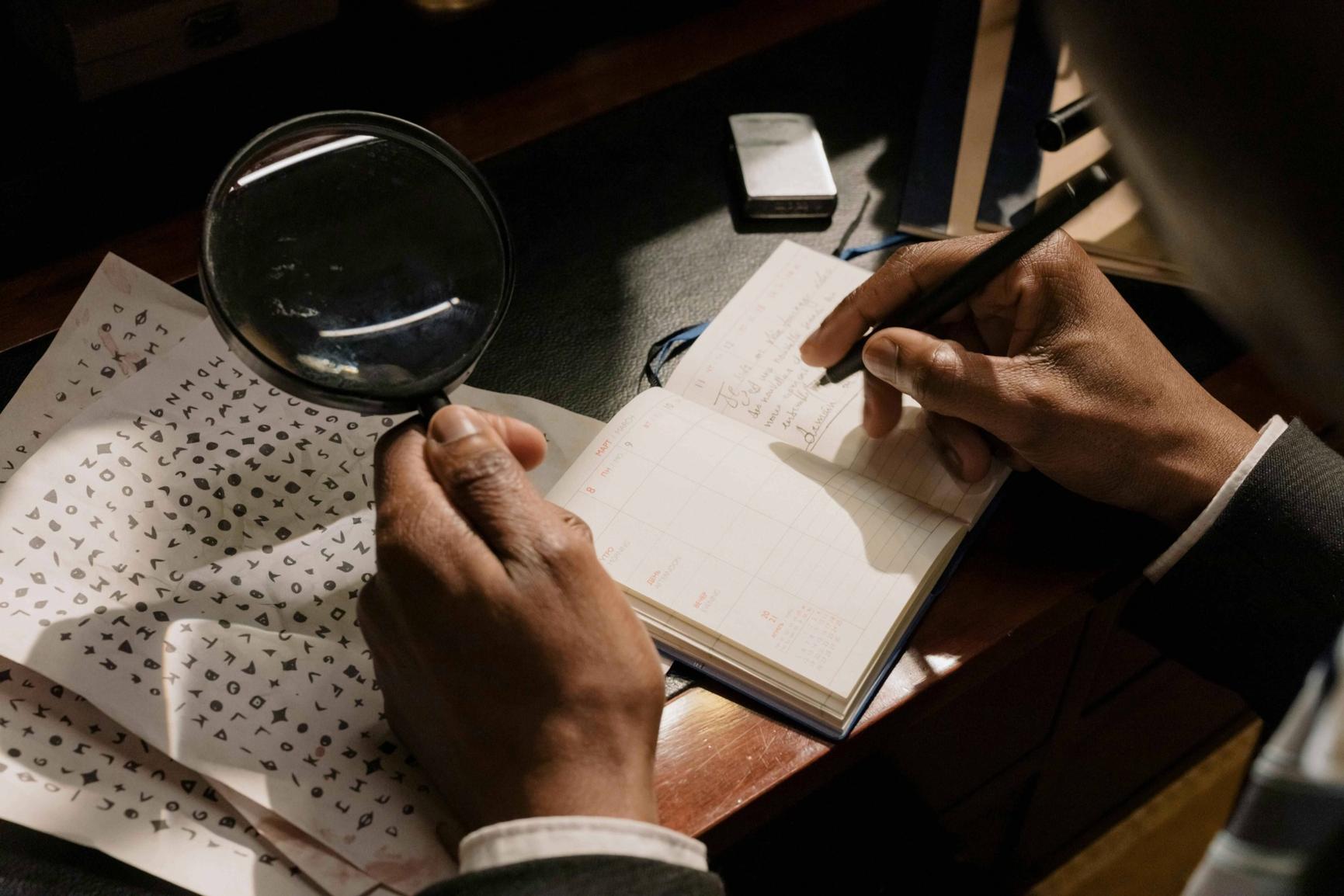

When a child is non-speaking or minimally speaking and cannot easily express needs or emotions, parents rely on subtle behavioural cues, movement, posture, shifts in tone or routine to understand what is happening. Over time, many parents become highly skilled at recognising these patterns, pre-empting distress, and managing sensory triggers. It is a role that demands constant vigilance, emotional insight, and a deep understanding of an individual child, much like the work of a skilled detective.

Why Parents Become Detectives

Executive functioning in daily life

Executive functioning challenges, particularly in working memory, limit how people communicate their needs. Autistic people without intellectual disability often experience various executive functioning differences, including difficulties with flexible thinking, emotional regulation, task initiation, and planning and organisation (Demetriou et al., 2018; Friedman et al., 2019; St. John et al., 2022). When intellectual disability is also present, executive functioning challenges tend to be more severe and emerge earlier in development (McClain et al., 2022). One of the most affected domains is working memory, the ability to hold and manipulate information over short periods of time. Difficulties in this area can affect a wide range of everyday activities, especially when combined with limited spoken language or adaptive communication. McClain et al. (2022) found working memory to be the most impaired executive function among autistic children with intellectual disability. These challenges will impact daily functioning in multiple ways, and, depending on the degree of intellectual disability, are likely to persist across the lifespan:

- Completing only part of a multi-step instruction (e.g., “Put your shoes on and grab your bag”) due to limitations in working memory.

- Losing track mid-task, such as forgetting why a room was entered or what was being done.

- Distress during changes in routine, linked to difficulty mentally rehearsing upcoming steps.

- Repeating questions or statements, not as a sign of obsession, but because information has not been retained.

- Difficulty with transitions, often resulting from limited recall of what is happening next and contributing to anticipatory anxiety.

- Struggling to follow conversations, particularly when multiple ideas are presented in quick succession.

- Requiring frequent prompts or reminders, support that may be misinterpreted as overdependence, inattention, or oppositional behaviour.

Understanding behaviour as communication

These executive functioning difficulties are further intensified when spoken language is limited, as is often the case for autistic individuals with intellectual disability (Schaeffer et al., 2023). In these situations, a wide range of alternative communicative behaviours often emerge. These may include:

- Withdrawal or avoidance, such as turning away, covering ears, or leaving a room.

- Increase or decrease in repetitive or self-stimulatory movements, such as rocking, flapping, or hand-flicking,

- Changes in body movements, pacing, or facial expression.

- Behavioural escalation may include self-injurious behaviour or sudden routine changes.

- Joyful or excited behaviours, including bouncing, clapping, or vocalising with smiles or laughter.

- Engagement in or avoidance of specific activities or routines.

- Changes in eating or sleeping patterns.

- Tone or rhythm of vocalisations, including pitch, intensity, or repetition.

Through sustained observation and relational attunement, parents become adept at interpreting their child’s behavioural communication. They rely on behavioural patterns, contextual cues, and environmental changes to understand expressions of pain, joy, frustration, or need, grounded in everyday interactions, essential for identifying distress, supporting regulation, and enabling participation. However, it is rarely acknowledged in formal systems, where standardised approaches often overlook the varied, context-driven, individualised ways non-speaking children express their needs. This work is emotionally demanding, particularly when subtle signs are missed and caregivers are left questioning what they did not see. Such moments reflect not parental failure, but systemic shortcomings, including inadequate professional training in supporting autistic individuals with intellectual disability. Families are frequently misunderstood in healthcare settings, with parents often left to interpret behavioural distress due to clinicians’ limited familiarity with non-verbal communication and contextual behavioural cues (Autism CRC, 2024; Department of Health, 2021).

Adulthood without adequate support

A national longitudinal study of autistic adults in Australia found significant disparities in adult outcomes between those with and without co-occurring intellectual disability. While 74% of autistic adults without intellectual disability were rated as having Very Good or Good outcomes, 80% of those with intellectual disability were classified as having Poor or Very Poor outcomes (Cameron et al., 2022). Autistic adults with intellectual disability were more likely to live in supported accommodation or with family, have limited access to post-secondary education, and participate in day programs rather than paid work or community-based roles.

Despite the support provided by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), families frequently report difficulty accessing services tailored to autistic adults with intellectual disability. The Autism CRC’s national co-design report (2024) highlighted widespread frustration regarding poor coordination between disability and health systems, particularly in rural and regional areas, and found that families often carry the burden of coordinating care, navigating eligibility, and managing service gaps. Families described ongoing challenges securing appropriate mental health care, transitional support, and consistent service delivery, even when NDIS funding was approved.

Research has shown that parents of autistic people with intellectual disability remain the primary providers of care and advocacy well into adulthood, often due to the absence of structured pathways to independence (Codd & Hewitt, 2020). Many parents continue to manage daily routines, prepare meals, oversee personal hygiene, accompany their adult children to medical and allied health appointments, administer medications, handle finances, support communication, coordinate services, advocate for access to appropriate housing or programs, and provide ongoing emotional and behavioural support. This enduring responsibility places significant emotional, physical, and financial strain on families (see Dückert et al., 2023; Hollocks et al., 2021; Vaz et al., 2021). The lack of inclusive and sustainable services not only limits opportunities for autistic adults but also impacts the long-term wellbeing of those who care for them.

The clinical imperative to interpret behaviour in context

Clinicians also face challenges in recognising distress, trauma, or unmet needs in autistic individuals with intellectual disability, particularly when communication is limited. PTSD, for example, is often overlooked due to the presentation of PTSD being different. For example, increased agitation or regression is frequently misinterpreted as behavioural issues (Kildahl et al., 2020). Similar difficulties arise when distinguishing autism from conditions like attachment disorders, complex PTSD, or emotionally unstable personality disorder (Sarr et al., 2024), and in identifying anxiety, depression, and trauma-related symptoms (Rodgers et al., 2012; Rumball et al., 2024; Hinze et al., 2025).

As with parents, clinicians must interpret behavioural cues that may be subtle, symbolic, or highly individualised. Accurate assessment requires attention to the person’s baseline, relational context, and long-term patterns, areas where families often hold critical insight. Effective support depends on collaboration embedded in curiosity, respect, and a shared commitment to understanding the person’s unique communication and needs.

Where to from here?

We recommend our on-demand course, Non-Speaking Autism. The course will equip participants with an understanding of life as experienced by a non-speaking autistic person, the reasons for specific behavioural and emotional reactions and the creation of an individualised plan to enhance the quality of life and well-being.

Participants in the course will learn practical strategies to encourage speech, the value of alternative and augmentative communication systems, how to acquire new abilities and coping mechanisms for accommodating changes in routines and expectations, sensory sensitivity, and social engagement, and how to express and regulate intense emotions constructively.

References

Autism CRC (2024). Report on research, co-design and community engagement to inform the National Roadmap to Improve the Health and Mental Health of Autistic People: Reimagining health services for Autistic people, their families and carers. Autism CRC.

Barratt M, Lewis P, Duckworth N, Jojo N, Malecka V, Tomsone S, Rituma D, Wilson NJ. Parental Experiences of Quality of Life When Caring for Their Children With Intellectual Disability: A Meta-Aggregation Systematic Review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2025 Jan;38(1):e70005. doi: 10.1111/jar.70005. PMID: 39763193; PMCID: PMC11724350.

Cameron, L. A., Tonge, B. J., Howlin, P., Einfeld, S. L., Stancliffe, R. J., and Gray, K. M. (2022) Social and community inclusion outcomes for adults with autism with and without intellectual disability in Australia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 66: 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12953.

Demetriou, E., Lampit, A., Quintana, D. et al. Autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis of executive function. Mol Psychiatry 23, 1198–1204 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.75

Department of Health. (2021). National roadmap for improving the health of people with intellectual disability. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-roadmap-for-improving-the-health-of-people-with-intellectual-disability

Dückert S, Bart S, Gewohn P, König H, Schöttle D, Konnopka A, Rahlff P, Erik F, Vogeley K, Schulz H, David N, Peth J. Health-related quality of life in family caregivers of autistic adults. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Dec 18;14:1290407. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1290407. PMID: 38193135; PMCID: PMC10773769.

Friedman L, Sterling A. A Review of Language, Executive Function, and Intervention in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Semin Speech Lang. 2019 Aug;40(4):291-304. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1692964. Epub 2019 Jul 16. PMID: 31311054; PMCID: PMC7012379.

Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Mar;43(3):629-42. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y. PMID: 22790429.

Hollocks MJ, Meiser-Stedman R, Kent R, Lukito S, Briskman J, Stringer D, Lord C, Pickles A, Baird G, Charman T, Simonoff E. The association of adverse life events and parental mental health with emotional and behavioral outcomes in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2021 Aug;14(8):1724-1735. doi: 10.1002/aur.2548. Epub 2021 Jun 2. PMID: 34076371.

Sarr, R., Spain, D., Quinton, A. M., Happé, F., Brewin, C. R., Radcliffe, J., ... & Rumball, F. (2025). Differential diagnosis of autism, attachment disorders, complex post‐traumatic stress disorder and emotionally unstable personality disorder: A Delphi study. British Journal of Psychology, 116(1), 1-33.

Schaeffer J, Abd El-Raziq M, Castroviejo E, Durrleman S, Ferré S, Grama I, Hendriks P, Kissine M, Manenti M, Marinis T, Meir N, Novogrodsky R, Perovic A, Panzeri F, Silleresi S, Sukenik N, Vicente A, Zebib R, Prévost P, Tuller L. Language in autism: domains, profiles and co-occurring conditions. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2023 Mar;130(3):433-457. doi: 10.1007/s00702-023-02592-y. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36922431; PMCID: PMC10033486.

St. John, T., Woods, S., Bode, T., Ritter, C., & Estes, A. (2021). A review of executive functioning challenges and strengths in autistic adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(5), 1116–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2021.1971767

Rodgers, J., Glod, M., Connolly, B., & McConachie, H. (2012). The relationship between anxiety and repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42, 2404-2409.

Rumball, F., Parker, R., Madigan, A. E., Happe, F., & Spain, D. (2024). Elucidating the presentation and identification of PTSD in autistic adults: a modified Delphi study. Advances in Autism, 10(3), 163-184.

Vaz, S., Thomson, A., Cuomo, B., Falkmer, T., Chamberlain, A., & Black, M. H. (2021). Co-occurring intellectual disability and autism: Associations with stress, coping, time use, and quality of life in caregivers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 84, 101765.